Fang’s Struggles with Identity

Fang, a third grader at the time, hesitated at a simple question. Her teacher waited impatiently, unaware of Fang’s internal conflict. She faced a dilemma. Since preschool, Fang had been officially registered as her eldest uncle’s daughter. Her birth parents had done this to avoid harsh penalties from China’s one-child policy, which was strictly enforced from 1980 to 2015. Scarred women dismiss Beijing’s pro-birth agenda.

By the time Fang reflected on the moment years later, she admitted, “I really had no idea which parents I was supposed to name.” She shared this with , using a pseudonym for privacy reasons. Fang’s confusion was a direct result of her parents’ efforts to protect her.

The Policy Changes

Lü Pin, a prominent feminist, commented, “Coercive family planning, as a form of state violence, has scarred women deeply… and people just haven’t got over it yet.” Lü, pursuing a doctorate in women’s studies at Rutgers University, noted that Beijing had yet to conduct any “open self-reflection” on the damage inflicted by these policies.

China gradually shifted its policy, increasing the birth limit from one to two children, and then to three in 2021. These changes aimed to counter the looming demographic crisis. Although the one-child policy ended, its effects persisted. Women like Fang, whose childhoods were marked by their parents’ struggles under the policy, now viewed parenthood with hesitation. This reluctance made Beijing’s current push for more births challenging to sell.

The Sacrifices of Eldest Daughters

Fang’s parents had avoided devastating consequences by hiding her birth. The penalties for having an unauthorized second child included steep fines, job loss, and even forced abortion and sterilization. At age 10, Fang finally returned home, but she remained registered as her uncle’s daughter. Her parents instructed her to maintain this identity whenever questioned.

After the policy ended in 2015, Fang’s parents attempted to have another child. They silently wished for a son, but her mother gave birth to yet another daughter—their third child.

Between 1980 and 2015, China’s one-child policy resulted in the disappearance of an estimated 20 million baby girls due to sex-selective abortions or infanticide. According to Li Shuzhuo, director of the Center for Population and Social Policy Research at China’s Xi’an Jiaotong University, the numbers were staggering.

Yao, another woman affected by the policy, shared a similar childhood experience. Born in rural Shandong, Yao was the eldest of three siblings. Her province allowed rural couples to have a second child, provided the firstborn was a girl. This “one-and-a-half child policy” emphasized the traditional preference for sons, with girls considered less valuable.

Yao’s mother secretly carried a third child, fearing the consequences of having an “extra” baby. After giving birth, she paid a crushing fine of 50,000 yuan (around $7,000) to register her son officially. Yao, however, lost nearly a year with her mother due to this policy.

From One to Three – or None?

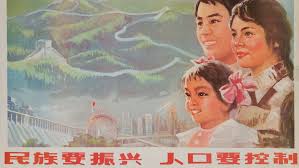

With the 2021 shift to a three-child policy, China launched campaigns to encourage births. The government, once focused on limiting families, now promoted pro-birth policies. Local authorities offered financial incentives, real estate subsidies, and extended maternity leave. Posters once discouraging more than one child were replaced with those advocating for larger families.

However, for many like Yao, the sudden reversal was frustrating. She sarcastically remarked, “How ‘well-planned’ the family-planning policy is! (The government) used to slap us for having two babies, and now expects us to have three?”

Fang, too, expressed irritation at the pro-birth push. “Having kids or not is purely a woman’s personal choice, not out of any policy, be it a stick or a carrot,” she argued.

Lingering Trauma and State Violence

Though China’s birth campaigns are now pro-natalist, many still carry the emotional and physical scars of the one-child policy. Online platforms like Xiaohongshu, China’s version of Instagram, have seen people sharing receipts of fines imposed for exceeding the birth limit. Childbearing decisions in China today remain colored by the trauma of the past.

Check Also: PS2 BIOS

Despite the state’s new approach, the shadows of forced abortions, sterilizations, and population control policies remain.